The Capital City Arts Initiative presented the exhibition Fables and Myths, with Elaine Parks and Sue Cotter at Western Nevada College’s Bristlecone Gallery from May 14 – September 10, 2025. The following is an essay by Chris Lanier for the exhibition.

Imagine, Dream, Ascend

This joint show, Fables & Myths, brings together work by Elaine Parks and Sue Cotter. They work in two very distinct modes – you would never mistake the work of one for the other –but they manage to strike up an interesting conversation with each other. I feel they occupy a similar landscape, but they traverse it in different ways. I had the opportunity to speak with both of them, and hopefully, some of their commonalities and their contrasts can be made visible in this essay.

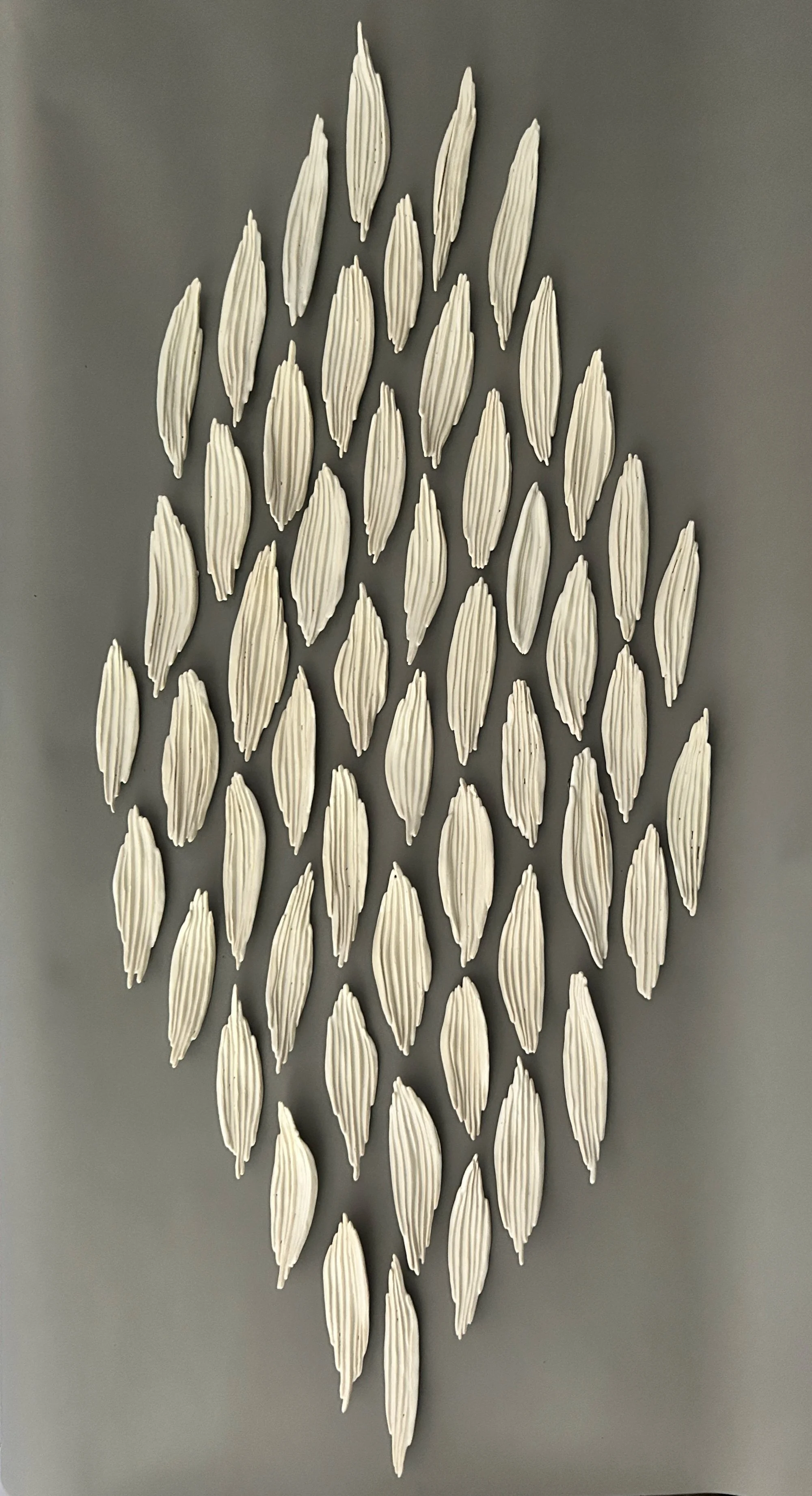

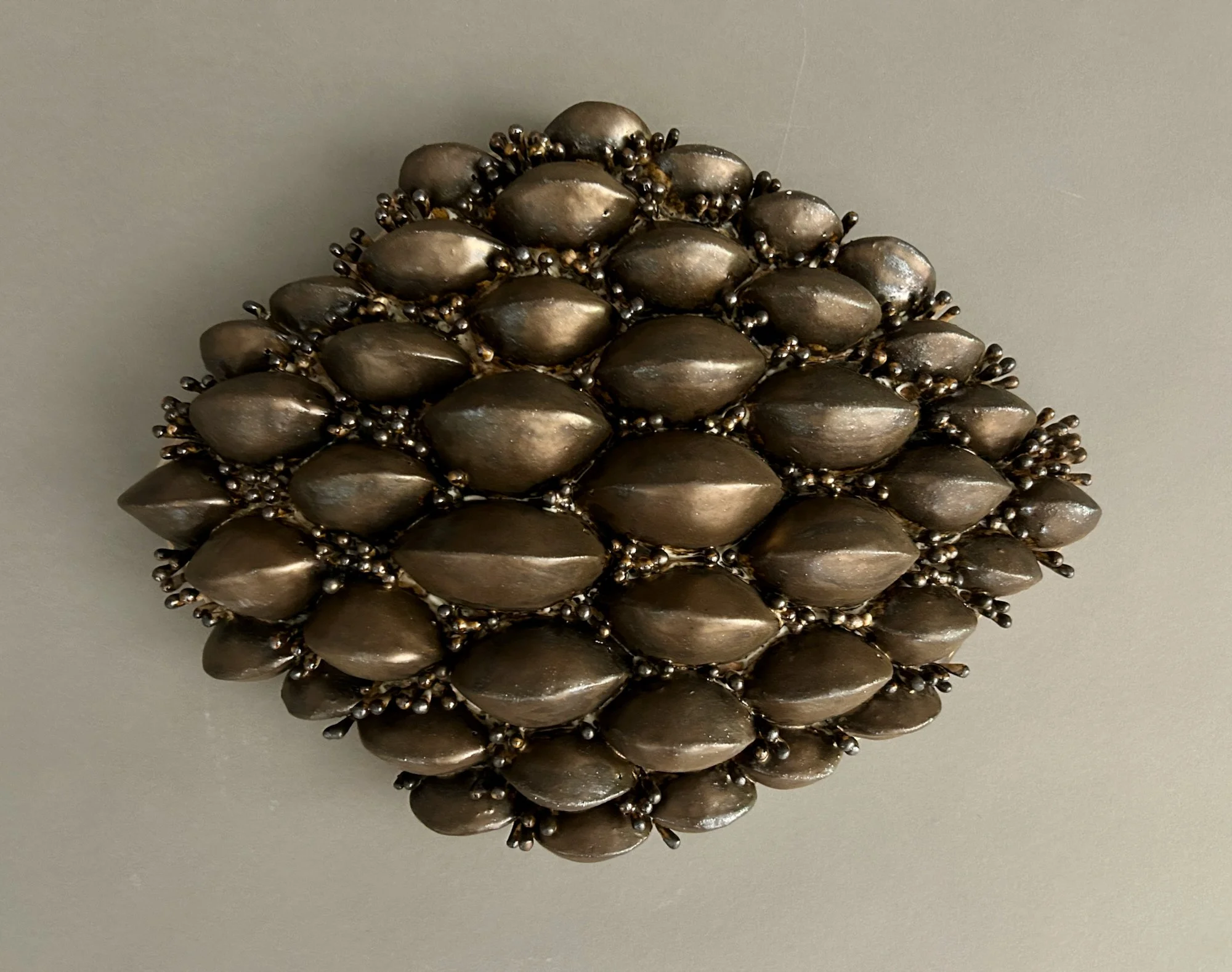

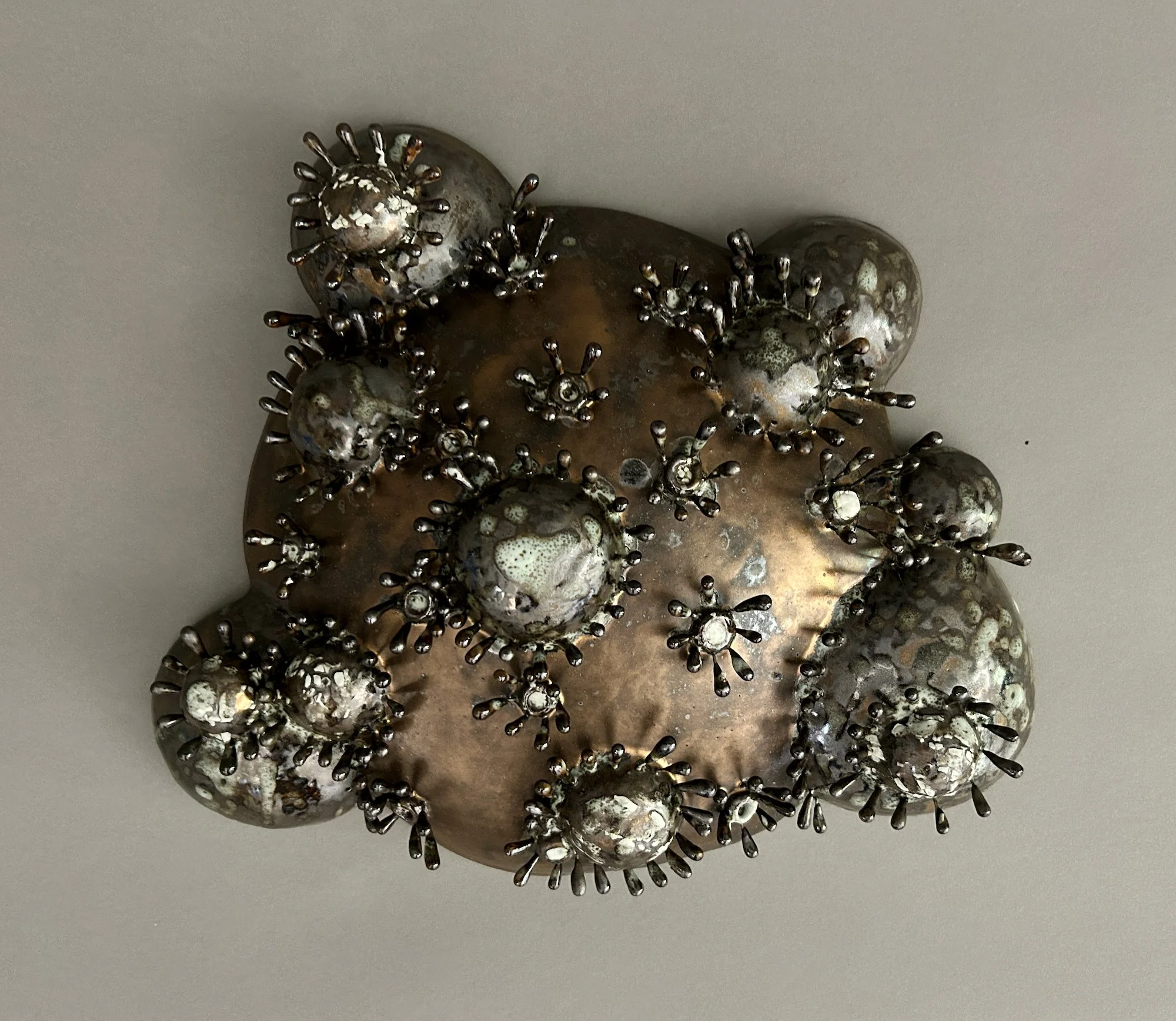

Elaine Parks’ work is connected to the textures and features of the desert landscape, but it functions in an in-between space, without convenient (or limiting) labels. Her sculptures look like natural objects that could be found on the desert floor, evoking stones, bones, nests, tufa formations, and so on – without quite aligning with any of those descriptors. They’re not representations of those things, but they adhere to a structural logic that can be found in those things. Parks isn’t a representative landscape artist, and she’s not an abstract artist, either. By making sculptures that are adjacent to recognition, she hopes to quicken the viewer’s attention. At a certain level, the sculptures are investigations into systems and textures of natural construction – as she puts it, she pays attention to “the way things are put together.”

Her present gateway to the desert landscape is Tuscarora, a small town north of Elko, with fewer than a hundred residents. She moved there about 25 years ago, from Los Angeles – the chair of the art department at California State University, where she earned her Master’s Degree, recommended it to her. “I wanted a change, and I got a big one,” she told me. “It was a quick decision to move up there, maybe not super considered, but it felt very much like home.” Living there, and going on walks, she’s aware of the changes that happen with the seasons, or even day to day, with adjustments of weather and light. “There aren’t distractions, and you can notice small changes. I’ll hike the same trail hundreds of times, but it’s always a little different. There’s always something to see. Sometimes it’s tiny and sometimes it’s huge. And that shifting perspective is interesting. It opens up areas of imagination to me.” The land, too, manages to disgorge traces of human history, from its mining era – like a body rejecting some alien element. “Every year, new stuff comes up – heaved up from the earth in the freeze and thaw. So the past is always coming up in an alive way. Suddenly, here’s this weird thing – what is it? What was it used for? Again, it just feeds into that imagination.”In this collection of sculptures, there is a play of forms that build on the surface of forms – the way fungi might sprout over a decomposing log, or the way barnacles might accrue to an underwater boulder –or the way lichen might begin to blanket a rock. The ambiguity of form can create confusion between desert and aquatic provenance, but Parks is aware that the distance between those poles is not, in some regards, that extreme. The Nevada desert was of course once underwater, covered by Lake Lahontan in the Pleistocene – in fact, Parks was recently commissioned by the Nevada Museum of Art to create sculptures in support of their exhibition Deep Time: Sea Dragons of Nevada, about Ichthyosaurs, whose fossilized remains are sequestered – like alpine fugitives – in the Nevada Mountains. Those fossils date back 225 million years, but the long-vanished waters of Lake Lahontan are accessible to Parks through sympathetic imagination. She notes the way language pulls those waters in – with terms like “the sagebrush sea” used to describe the territory. The mine tailings deposited in the landscape remind her of whales breaching the flat surface of the land. There’s also, closer to the skin, the way the open scope of the area invites those sensorial comparisons, something she’s attuned to in her desert walks in Tuscarora. “It has the vastness of an ocean. I love the deep past informing the present – you can feel it somehow. I grew up on the coast, and I get the same feeling swimming in the ocean as I get walking in the desert –that insignificance. I love that feeling.” This work does play with a sense of self-erasure. I suspect Parks would consider it a success if a viewer were unable to detect, in her sculptures, the mark of a human hand – if the viewer were to presume the sculptures were found objects, and not created ones. Sometimes the surfaces are actually shaped by natural objects – she’ll use a rock to create a texture on a clay surface, using clay as a receiving medium, like a printing surface. For years, she didn’t sign her work – finally giving in, “because you’re supposed to.” Her aim is not to use clay to display some form of mastery – to use it to mimic reality, and (in an expression of artistic egotism) to surpass or replace it. It’s not about fooling the senses or reproducing natural forms – but pursuing a self-sufficiency of form. The sculptures are in pursuit of an object that is – as she puts it – “in itself complete. It had a maker, but it’s its own complete thing, without its maker.”

SUE COTTER

A good portion of Cotter’s work is in the book arts – and some of that work has been incorporated into the show, where the viewer isn’t able to sit down into a comfortable chair to leaf through their pages, but where they get to exist as sculptural items, giving hints of their contents, but more frontally presented as beautiful, potent objects. There are also more traditional sculptures on display, including several iterations of Cotter’s mythological character Thel, a human figure with a bird’s head. These depictions of Thel have a totemic quality – one sculpture presents Thel adorned with a halo made from a bicycle gear. Thel is named in homage to the titular character in William Blake’s The Book of Thel. Blake is probably best known for his poetry, most especially “The Tyger,” whose lines “What immortal hand or eye / Could frame thy fearful symmetry?” are among the most-quoted lines in English poetry. Blake is also – as Cotter pointed out to me – something of a patron saint among Book Artists, having produced and printed much of his poetry as self-made illuminated manuscripts. He etched his own plates with drawings and text, and hand colored (along with his wife Catherine) the printed pages with watercolor washes. In Blake’s illuminated book, Thel is a young shepherdess, suspended between an airy, spiritualized existence and the physical realm, with its terrible certainties of death and decay. She is a figure caught between worlds. Cotter has adopted Thel into her own cosmology, retaining the original figure’s sense of being “of the air” by literalizing her avian aspect. As such, she appears as a figure from mythology, which abounds with hybrids of human and animal forms. When I asked Cotter what makes a character a mythological figure, as opposed to a merely fictional one, she explained it had to do with occupying multiple worlds – ¬ the mundane one, and the realm (or realms) beyond it: “The mythological world is connected to other worlds, parallel worlds.” A bird, in itself, suggests a comfort in multiple worlds – “Being a bird is an ability to be in the air and on the ground – to be above it or to be in it.” Thel also exists as drawings in some of the books on display, which play with details of topological maps, finding animal or human outlines in their elevation contours. This is how Thel would see the world – from an aerial vantage point. Another set of work is done in assemblage – a type of sculptural collage, pioneered by Joseph Cornell, an artistic hero of Cotter’s. Cornell would piece together collections of found objects, making poetic dioramas framed in salvaged cases, or cases he constructed himself. Many had multiple compartments, suggesting a system of classification and organization, though his sense of order was never clinical or sterile. At most, the compartments suggest a grammar, built to scaffold a constellation of associations. In Cotter’s assemblage Eucatastrophe, that framing grammar is literally linguistic – its structure is provided by a type case, a box ordinarily used to store and sort the letters used in a movable type printing press. The cells of the type case contain neatly arranged disasters – crumbling walls, tiny inoperable cars, clusters of keys with no hope of finding their intended locks, vacant windows that seem to be performing miniaturized recursions – boxes within boxes within boxes, a finely tuned itemization of emptiness or detritus. The total effect is of an apartment block that was bombed out – still clinging stubbornly to its hive-like superstructure, but fundamentally uninhabitable. There is a respite from this, however, in the upper right quadrant - one rectangle that, in the warmth of its colors – and the sense of a vacancy that has been recently departed and will be shortly returned to – asserts itself as an oasis. It depicts a cozy room, with a tall, well-stocked bookcase, next to which is a small window – the only one, in the assemblage, that suggests a blue sky beyond its panes. This refuge, with its small personal library, once more gestures to the movable type press, which – for all its mechanical details, was a technology of intimacy. Beyond the production of books, it produced this domestic tableau, where an individual, in their private home, could commune with an author. Eucatastrophe was worked on, over the span of a couple of years, during the Covid lockdowns, and is suffused with the atmosphere of that time – where it could feel that you weren’t living in a society, but rather living in society’s coat-pocket. The last set of work by Cotter is a series of stone books. Cotter has been making these stone books for many years, ¬ whose covers are split rocks that she finds in the landscape – she relates these works to the longstanding Chinese tradition of collecting and displaying “spirit stones,” or Gongshi stones, often placed on a small pedestal. These stones are admired for their aesthetic, and even spiritual, qualities. In Cotter’s work, she cuts paper to conform to the shape of the rock, so that the pages of her bound volumes appear as intervening strata. It invites the viewer to regard writing as a fundamentally sedimentary act, with the slow accrual of words rather than minerals – which strikes this writer as fair. The content of the books is landscape-related collage images, and some text explaining her process of making these books and collecting the stones. These spirit rock books perhaps provide the most direct contact point between Cotter and Parks – a bridge between a found geology and an invented geology. Cotter’s work is deeply involved with narrative – Parks’ work almost eschews narrative, presenting a topology that seems sufficient to itself. She creates objects that aspire to exist comfortably outside of any necessity of human explanation or the amendments of language. But both artists’ work can meet on some common textures and territories – both, I think, pay a deliberate fidelity to the mute bedrock foundations of reality. And, crucially, that fidelity isn’t a constraint – rather, it’s solid ground from which to imagine, dream, ascend.

Chris Lanier

Reno, Nevada

May, 2025